Day one of the joint appearance from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on Capitol Hill didn’t surprise anyone, but did lay out the current blueprint for U.S. economic policy. Monetary policy will be loose until there is “maximum employment,” and fiscal policy will be aggressive, though Yellen made clear that the White House wants to pay for increased infrastructure investment with higher taxes.

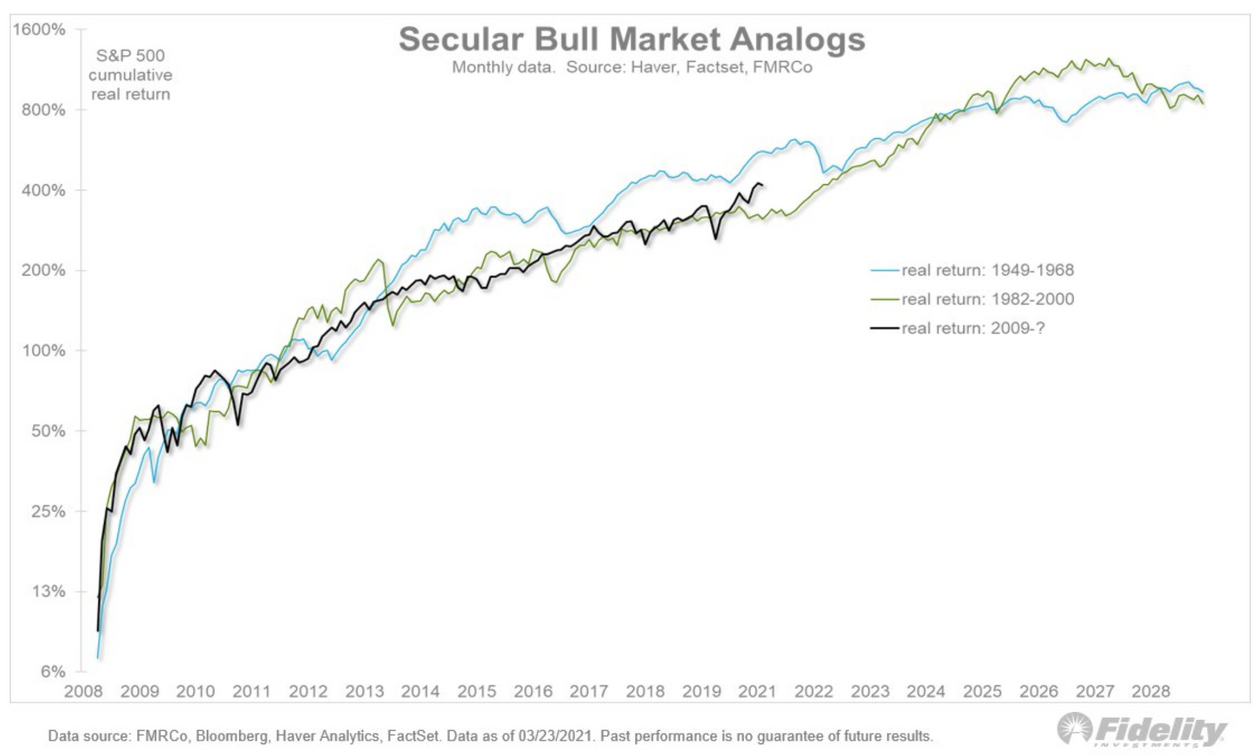

Jurrien Timmer, director of global macro for Fidelity Investments, says fiscal and monetary policy “will remain at full throttle for some time to come.” When this column last heard from Timmer,he was saying that the 1960s provide a blueprint for what’s to come for the stock market. He updated that chart to show it is still on track.

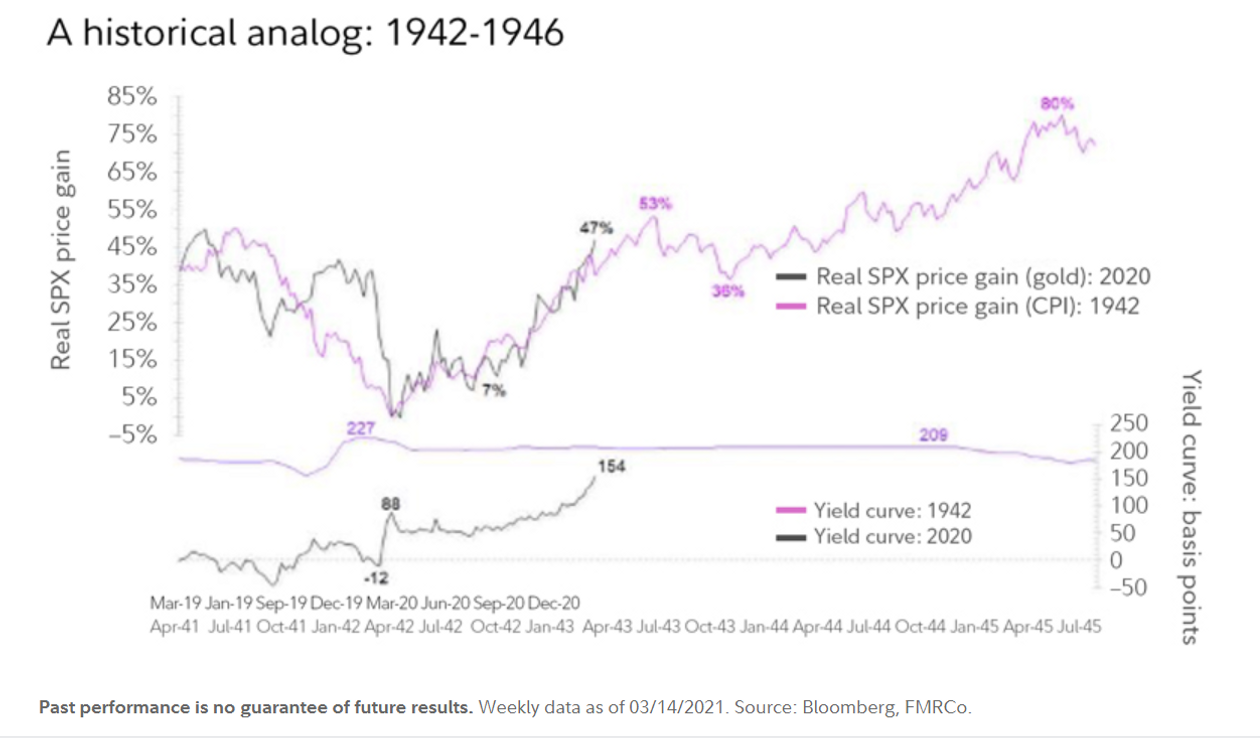

But another historical analog is the 1941 to 1946 period. To mobilize against World War II, federal debt tripled, the Fed’s balance sheet swelled by 10-fold and the Fed capped both short- and long-dated interest rates below the rate of inflation. Granted, the current playbook isn’t quite that aggressive — the Congressional Budget Office’s forecast for the national debt in 2030 is only 6% higher than it was before the COVID-19 pandemic — but directionally it is similar.

“The net result of the Fed’s rate suppression in the 1940s was that real rates fell well below zero and stayed that way for a number of years as inflation took root. In my view, the Fed today will accept higher inflation, as will the Treasury. How else is the country going to get out from under its rising debt burden,” says Timmer.

The result was a surging and broad-based stock market, at least until inflation got really carried away later in the decade. There also was a steeper yield curve, as measured by the gap between 2- and 10-year yields.

Comments